Digital dementia, the essence of technology and re-rooting in nature

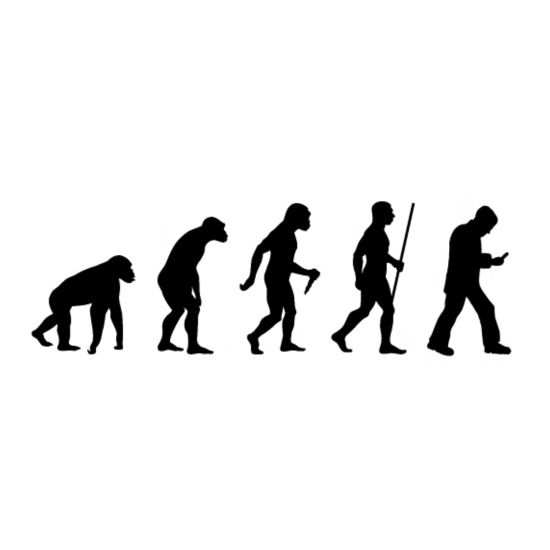

I would like to share my thoughts by addressing the issue of a phenomenon called “digital dementia.” The term digital dementia was introduced by the German neuroscientist Manfred Spitzer, who adopted the term from South Korean researchers and made it known with his best-selling book with the same name in 2012. Originally the term “digital dementia” was referred to as the loss of the collective memory of cultures. Spitzer extended this understanding to a loss of cognitive functioning – thinking, remembering, reasoning and behavioural capabilities to such an extent that it interferes with a person’s daily life and activities. In his book “Digital Dementia” Spitzer talks about various effects that, in his opinion, occur through the overuse of digital media: Reduction of social interaction, reduction of social participation, loneliness, forgetfulness, lessened well-being, less physical movement, anxiety, depression, aggression, ineffectiveness, short-term memory loss, reduced written language skills. Further, it leads to considerable potential for addiction and particularly leads to the destruction of relationships. There has been a controversial reception of Spitzer’s book, but the position that through digitalisation, in particular children, can no longer develop to become healthy adults has been heard louder than ever.

I want to ask some basic questions regarding digitalisation. What is digitalisation? It is a technologization – and what is technology and how does it affect our humanity? Did something develop which can be called a “digital world view” or “digital mentality”? Do we, humans, still control the digital tools we use, or do they control us? Do they give us a deeper access to reality, or do they limit this access? As a matter of principle, we should philosophically question our actions regarding technical developments such as the use of digital technologies, inasmuch as they have an effect on our humanity. We should also ask ourselves the question: Do they better us as human beings? Do they help us to grow in virtue? Or might they actually contribute to a dehumanization of society? These are the questions I intend to answer as far as possible.

Digitalisation is rationalisation and technologization

We are undoubtedly living in a time of unprecedented technological change. We all know of the Industrial Revolution and it has not been reflected that we are experiencing a Digital Revolution and what the effects of this are. This digitalisation is part of technologization. From the German speaking word, which knows a more sceptical and pessimistic tradition concerning technological developments, although nowadays, in particular in modern Germany, there is a strong belief in scientism and technological developments, which is part of two phenomena which we call modernisation and globalisation. I want to add in opinion there is not a real reflection and debate, not to speak of a critical reflection of the issues at hand.

In order to better understand the issue at hand we might want to have a closer look at the fundamental changes in the view of the world, the weltanschauung, and of how we see ourselves as human beings as the result from the growing scientific knowledge and the effect it had on ways of thinking, living and being. It was about 300 years ago in the time of the Enlightenment and its rationalism that the two strong impulse for the development of natural science and also technology surged. It was in fact the very intention to make use of scientific knowledge for practical purposes – of (old) Greek would call techné, which he distinguished from the two other forms of knowledge, namely theoria and poesis. For instance, two German thinkers, namely Max Weber (1864-1920) and Max Scheler (1874-1928) have pointed out that the modern natural sciences owe less to a theoretical impulse of newly emerging curiosity than to the practical impulse of making the world technically usable. René Descartes (1596- 1650) clearly expressed this new world view when he spoke about a domination of the world, that would make humans masters of the world:

“It is possible to gain a knowledge that is of great use in this life. Instead of the theoretical philosophy now taught by the scholastics, we can find a practical one by which we can know the nature and behaviour of fire, water, air, stars and sky, and all other bodies that surround us, and use these things for all the purposes they can serve. Thus, we make ourselves masters and owners of nature.”

We can state with Francis Bacon (1561-1626) that technologization has led to “facilitation of the human condition.” As a result of this development “science” as we understand it today is subject to the standard of an explicable, measurable, and thus “quantitative” objectivity. In the last century the two German thinkers of the Frankfurt School, Max Horkheimer (1895-1973) and Theodor Adorno (1903-1969) spoke of “instrumental reasoning.” The consequence of this absolute rationality is that it can no longer see anything for itself and allow it to be valid; everything is seen under the categories of means and useful ends – techné instead of theoria. This leads, according to the two mentioned thinkers, to an equation of a meaningful and useful existence. We can also speak of an “hermetic expediency” (German: eingeschlossene Zweckmäßigkeit), which leads to the temptation to see the world to be at man’s disposal, to want to get things under our control and thus make man the subject of man. Such a “scientistic belief” in the natural sciences and their possibilities prevails today – it very much forms the way we are at present. Politically speaken, this leads to a technocracy.

It was particularly also Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) who described the essence of science and technology and spoke of a “planetary technology.” They both have a specific way of discovering being. Characteristics of the scientific approach are calculating, objectifying, imagining, and ascertaining. These characterise their way of seeing and questioning natural processes. In this way what is an object becomes an object vis-à-vis a subject, only “what thus becomes an object, is, is regarded as being.” In this way, man in turn becomes the “measure and centre of being.” This central position of man, however, in turn reinforces the modern subjectivity that began with Descartes. Only what is revealed in this way of understanding the world is recognised. This thinking also applies to technology. As man is forced to be a subject through objectification, the world loses its richness of meaning and reference and what exists degenerates into mere raw material for the human subject. The central role in which man imagines himself to be within world events also serves to increase the will for technical controllability and availability:

“Man is on the verge of throwing himself upon the whole of the earth and its atmosphere, of usurping the hidden workings of nature in the form of forces, and of subjecting the course of history to the planning and ordering of an earth government. The same rebellious man is unable simply to say what is, what this is, that a thing is. The whole of being is the object of a single will to conquer.”

The essence of technology according to Heidegger

It is this dominion character of modern technology which Heidegger focuses on in his analysis and which worries him, while not being against technology as such, but trying to understand it better. Famously in one of his word creations Heidegger spoke of the Gestell, which can be translated as enframing, which for him is the essence of modern technology. Heidegger describes the technical and objectifying thinking as the imagining thinking in the sense that this thinking brings the being as an object before itself and at the same time conceives of it in the temporal mode of the present as existing for it. Thus, by means of technology, man places nature before himself as a mere resource. He does this by using technical means, whose totality Heidegger calls Gestell.

Heidegger speaks of the “utilisation as a consumption” (Nutzung einer Vernutzung) and as its goal its own aimlessness. And this is what one can observe today, technology dominates our society; Heidegger spoke of the dominion of the being of modern technology, which thus is no longer neutral. This is where the danger lies, when it is the only means of acquiring truth, or in the words of Heidegger: “of unhiding being”. This totalisation of technology as sole method has the potential for universal annihilation. As a counterexample Heidegger sees the activity of an artist, who also unhides reality, namely beauty. But unlike art, technology disguises the access to knowledge, reality, and truth.

If we follow the train of thought just expressed, it is natural that a dominion of the technological process goes along with a loss of truth and accordingly the truth about man and virtuousness. Heidegger said that man comes under the wheels – he is degraded to a purchaser of a stock. In extreme cases man becomes a resource himself and as such he is only of interest as far as he can be made serviceable as “human material”, a term which is close to the term “human capital”, which is often used nowadays. And in this process is it not only man, but technology itself puts (stellt) the things – it is the Gestell, the enframing. This loss of truth ultimately means a loss of self.

One of Heidegger’s students, the German-Austrian and Jewish philosopher Günter Anders (1902- 1992), focused in his research on the potential of the destruction of humanity through technology. He observed a growing discrepancy between the imperfection of man and the ever-increasing perfection of machines, which for Anders are also not value-neutral means to an end. Machines have positive and negative effects, they lead to a facilitation of work, as well as the disappearance of the purposefulness of work. Anders focusses his critique on three fields: the atom-bomb, television, and morality. For instance, television always shows only part of the facts, never all of them; reality becomes a distorted image, in which eventually lies become truth. Generally, according to Anders, the technically changed world has liquidated previous forms of morality. The task of our epoch is to give people sovereignty over the machine and to avert impending nuclear, technical, and ecological catastrophes. However, he does not call for blind hostility to technology, rather for sensible reflection.

To summarize the pessimistic analysis of the effects of technology: Man no longer stands in his original relationship to being as the one addressed by disenchantment and uprooting us from nature – in which lies a great danger. However, in danger grows that which saves, as the German poet Hölderlin said:

“In the face of the homelessness (Heimatlosigkeit) of the human being, man’s future fate is revealed to the thinking of the history of being in the fact that he finds his way into the truth of being and sets out to find it.” (Heidegger)

The possibility of conversion: re-rooting in nature

Heidegger and other thinkers clearly warned of the dangers of “technological ways of being” that can lead to a dehumanization and a world that loses its richness of meaning and reference. It particularly also leads to a loss of transcendence – shortening of the possibilities of the human spirit, thus making man limit his own possibilities, fostering mediocrity and narcissism. However, we can counteract these effects. We can examine our relationship towards technology. Heidegger used particular words for the possibilities, namely Kehre, Einkehr, and Heimkehr, return, retreat, and homecoming, or in other words: re-rooting in nature. Nature clearly is the biological nature, but it also is the metaphysical nature of man, what philosophy calls the anthropological question.

One way to re-root is to evaluate technology. Famously, Heidegger said that science and thus also technology do not think, they are mindless. With Wilhelm Dilthey (1833-1911) Heidegger also made the distinction between the natural sciences, which explain things (erklären) and the human sciences which understand (verstehen). Physics for instance explains to us that we can do with the iron of a hammer, but it does not help us to understand what a hammer is, nor to which end we ought to use it. Thus, natural science and technology remain disconnected to certain aspects of real life, which is conditioning our perception of reality. Therefore, in the words of Pope Benedict XVI, who also pleas for a return to the common wisdom of the great cultures:

“We must learn to understand again that the great moral insights of humanity are just as reasonable and just as true, indeed, are truer than the experimental insights of the natural scientific field.”

In other words, there is a “utility-rationality” and “value-rationality”. The value-rationality is connected to the psyche and spirit (Geist) of man, which enables the development of our personality. It is also connected to the dimension of our feelings and thus of empathy. Heidegger would speak of a “clearing of being,” to bring something into appearance, truth, life, and revelation. Bringing forth something the Greeks called physis. There is a potential in us that can come into being, which very much touches the dimension of virtues as a true way of human life. Dilthey in his distinction of natural science and human sciences pointed out that there is one vital dimension of partaking in a human existence and that is experience (erleben):

“As an object of the humanities, however, it only arises insofar as the human condition is experienced, insofar as they are expressions of life and insofar as these expressions are understood.”

This means that there is a relational context of our existence. In the modern outlook, the “technological ways of being”, we run the risk of partitioning ourselves away from a unity of I, you, and the world – what the Greeks call the cosmos. In a pre-modern understanding for instance, the trees were my home, ultimately, they were used to create a home and thus, when they were used, there still was a relationship. They are not an abstraction, which we use as a resource. This is what modern thinking failed to see; its concern is mainly productivity, which is a mindset that also threatens the authenticity of life. This modern thinking as Descartes expressed makes a strong, wrong, and dualistic disconnection of the subject and the object, it particularly fails to see the relational dimension which would include seeing the importance of the other. According to Heidegger it fails to see how to work with nature to create something, for which he uses the Greek word poiesis, which was more in line with poetry. And more than that the modern way of thinking and being fails to see the sacred dimension of the other, because it ultimately does not want to see the divine dimension of creation. One expressed possibility to re-root is a deeper reflection on human nature and thus also of virtue as such and how it is part of our human nature, a reality is more difficult to grasp through a “digital worldview”:

– According to the Classical tradition, virtue is seen in the context of social and moral action. Virtues are habits that are acquired by frequent practice. Morality remains dependent on social interaction and personal responsibility, which digital technologies with its unpersonal being limit.

– By contrast, technologies as tools we use lack a contemplative dimension. Contemplation refers to thinking profoundly about something, such as the final goals of one’s actions or the purpose of life. Dealing with these questions has a teleological and religious dimension free of utilisation.

– Technology makes life easier, which gives man help. However, as Plato points out in his allegory of the cave, the acquisition of true knowledge (including virtue) is not a easy-going, but also painful, educational process of inner transition. In other words: It requires an existential transformation for which human experience is needed, which can only be acquired in real life. The process of acquiring virtues and the true knowledge about them is thus neither a purely intellectual, formal nor abstract act.

– Aristotle stated:

“It is not the Logos, as others think, that is the beginning and leader of virtue, but rather non-rational passion. Because the precondition is that a certain irrational impulse is created in us, which is indeed the case, and then, on this basis, the Logos must, as a second instance, bring the matter to a decision.”

The irrational impulse normally is an appreciation and empathy for a certain person or idea.

Practically re-rooting in nature

Digital media can be very useful and a good tool, in particular for education. Yet, it can become problematic and damage our brains. Examine yourself: How do I perceive the world; how do I see the world? Is the world only a resource for me, at my disposal to be exploited? Or am I in a relationship with it as a respectful partner in the cosmos? May I actually contribute something good to it and to others? Do I take responsibility? Do I give love?

Reconnect with the world, the cosmos, as far as possible! Live in reality! Experience life! In the words of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900): “Be faithful to earth.” This makes it possible to perceive a deeper reality and thus also meaning. Open your senses for the beauty of life – be astonished! Regarding the physical dimension of our existence and at the same time the inner dimension of the soul:

– Do a daily workout – move your body. (Particularly endurance sports promote brain function.) Have an upright posture. Try to do certain exercises such as sit-ups and push-ups on a daily basis.

– Improve your time management and avoid spending unnecessary time in front of your computer, TV or your Smartphone. (Is it necessary to have a smartphone? It is easier to renounce a desire completely than to want to be moderate in it). Aim to deal with technology in such a way that you have more time for yourself and the growth of your soul. Read books.

There is nothing that replaces interpersonal interaction, particularly for growth in virtues such as temperance or wisdom. Interact in dialogues. Relationship to the whole is not simply one of intellectual rational understanding but involves an affective disposition that is made up of a sense of respect, reverence, veneration, awe, and modesty. All these virtues are only acquired by regularly practicing them, so that they become a habit and are imprinted in our character. Also contemplate on your goals and the meaning of life. Ask yourself: Why I am here, what is my purpose – what makes me human?

Text als PDF-Datei runterladen